Refactoring: Why Your Future Self Will Thank You

Nod if you have ever written a “harmless” quick fix to meet a deadline while signing a blood pact with the God of Deadlines that you’ll clean it up later. Fast forward a few months, and suddenly every change feels like a high-stakes game of Jenga. You pull one variable out of a function, and the whole system starts wobbling. You hold your breath, pray the build stays green, and realize that one more “quick fix” is going to trigger the total collapse of civilization within this codebase. If you are one of the non-nodders, you can close this now. (Also, teach me your ways, oh perfect one.) But to my nodding friends: let’s talk about the debt you owe to your future self. Because right now, the sins of your past are here to collect, and the technical debt collector doesn’t take IOUs—he takes sleep, sanity, and possibly your weekends. The Resistance: How to Fight Back So now it’s war, and let’s be honest—you’re currently on the losing side. The Jenga tower is leaning at a 45-degree angle, and the “civilization” of your codebase is one semicolon away from an apocalypse. Now we aren’t going to fix everything in a day (that’s how you lose a Sunday), but we are going to stop the bleeding. The “Rule of Three” (Your Early Warning System) Before you go scorched earth on your files, use the rule established by Martin Fowler. It’s the easiest way to know if you’re “polishing” or actually “refactoring.” The First Time: You just get the damn thing to work. You’re a hero. The Second Time: You wince while copy-pasting, but you’re in a rush, so you do it anyway. You feel a little dirty, but the tests stay green. The Third Time: STOP. If you do it a third time, you aren’t delivering value; you’re just digging your own grave. This is the moment the resistance begins. Move 1: The Extract Method The first weapon in our arsenal is the Extract Method. If a function is so long that it has “chapters” (you know, those big chunks of code separated by helpful comments like // Save to DB), it’s too big. The Strategy: Take those chapters and turn them into tiny, well-named functions. The Jenga Block (Before): function completeOrder(order) { // Logic to calculate tax… // Logic to save to database… // Logic to send email… } The Solid Foundation (After): function completeOrder(order) { const tax = calculateTax(order); persistOrder(order, tax); notifyCustomer(order); } Move 2: The Guard Clause (The “Bouncer” Strategy) If your code looks like a sideways pyramid of if-else statements, you aren’t writing a program; you’re building a labyrinth. Every time you nest an if, you force your brain to remember one more “state.” By the time you reach the actual logic in the middle, you’ve forgotten why you were there in the first place. The Strategy: Use Guard Clauses. Instead of wrapping the “good” code in layers of conditions, check for the “bad” stuff first and exit early. Think of it as a bouncer at a club—if you don’t have the right shoes, you aren’t even getting in the door to see the band. The “Death Star” Nesting Block (Before): This is what happens when you try to keep everything “safe” by wrapping it in blankets. By the time you get to the actual transferFunds call, you’re indented so far to the right that your code is practically falling off the screen. function processWireTransfer(account, recipient, amount, userToken) { if (userToken.isValid) { if (account.status === ‘ACTIVE’) { if (account.balance >= amount) { if (recipient.isVerified) { if (!account.isFrozen) { // After 5 levels of nesting, we finally do the work const receipt = transferFunds(account, recipient, amount); sendNotification(receipt); return “Success”; } else { return “Account is frozen”; } } else { return “Recipient not verified”; } } else { return “Insufficient funds”; } } else { return “Account inactive”; } } else { return “Unauthorized”; } } The “Bouncer” Resistance (After) We stop asking “Is it okay to proceed?” and start saying “Give me one reason why I should kick you out.” We handle every failure case at the left-most margin. function processWireTransfer(account, recipient, amount, userToken) { // Bouncers clearing the line if (!userToken.isValid) return “Unauthorized”; if (account.status !== ‘ACTIVE’) return “Account inactive”; if (account.balance < amount) return "Insufficient funds"; if (!recipient.isVerified) return "Recipient not verified"; if (account.isFrozen) return "Account is frozen"; // The VIP logic: No nesting, no confusion, just work. const receipt = transferFunds(account, recipient, amount); sendNotification(receipt); return "Success"; } Why the Resistance loves this: The “Exit Early” Mindset: You deal with the “garbage” cases immediately. Once you pass line 3, you know the token is valid. Once you pass line 6, you know the funds are there. Zero “Else” Debt: Notice that the else keywords completely vanished. You don’t have to scan down 20 lines to find the else block that belongs to the first if. Cognitive Load: In the first version, your brain has to hold 5 conditions in a “mental stack.” In the second version, you only ever care about the line you are currently reading. Scalability: If the bank adds a new rule (like “No transfers on Tuesdays”), you just add one more bouncer at the top. You don’t have to rebuild the entire pyramid. Move 3: The “Plain English” Protocol In the heat of a “quick fix,” we tend to name things like we’re being charged by the character. We use variables like d, data, or the dreaded temp. In a collapsing civilization, these are the broken street signs that lead the rescue team into a dead end. The Strategy: Use names that describe intent, not just data types. If a variable holds the days until an account expires, don’t call it d or days. Call it daysUntilExpiration. The Cryptic Code (Before): function check(u, l) { const d = new Date(); if (u.lastLogin < d - l) { return true; } return false; } The Resistance Intel (After): […]

Temporal.io for Long Running Jobs

What are long running jobs? A long-running job refers to any task that takes more than a few seconds to complete. Running such tasks directly within a web request can lead to timeouts and a poor user experience, as the request may hang or fail before the task finishes. To maintain application responsiveness and reliability, these jobs are usually offloaded to background processes or queued systems where they can run independently without blocking user interactions. Why they are painful in traditional systems? Imagine you’re baking a massive cake, but your oven can only bake one thing at a time. A “long-running job” is like that giant cake – it takes up the entire oven for a long time. In traditional systems, these jobs are a problem because they tie up the whole system. While that one job is running, other, smaller tasks have to wait their turn. It’s like a line at a checkout counter where one person is paying with a million coins – everyone else is stuck waiting. For example: A traditional system might have to generate a large number of payslips at the end of the month. This task could take several hours. During that time, the system might be too slow to process customer orders or update inventory, causing a bottleneck for everyone else who needs to use the system. How Does Temporal.io Fit In? Whether it’s a background task that retries payments, a multi-step user onboarding flow, or a report that takes 20 minutes to generate, traditional solutions often fail under real world complexity. You end up cobbling together: Message queues (RabbitMQ) Background workers (Hangfire) Retry logic (often custom) State storage (usually a DB table) Monitoring (if you remember) It works – until it doesn’t. Jobs get lost. Crashes corrupt progress. Debugging is a nightmare in traditional systems. What is Temporal? Temporal.io is a platform built to handle long-running, durable, resilient workflows – all through plain code. You define workflows and activities as regular functions. Temporal takes care of: Durability: State is persisted automatically Retries: Built-in and configurable Fault tolerance: Workers can crash, jobs won’t be lost Timeouts & cancellation: First-class features Observability: Comes with a web UI out of the box Core Concepts in Temporal.io Workflows In Temporal, a workflow is a piece of code that orchestrates a series of tasks, known as Activities, to complete a larger process. Defines what needs to happen and in what order. It is like movie script. Example: “First welcome the customer, then process payment, then send confirmation.” // workflows/onboardingWorkflow.ts import { proxyActivities } from ‘@temporalio/workflow’; import type * as activities from ‘../activities’; const { sendWelcomeEmail, processPayment, sendConfirmation } = proxyActivities({ startToCloseTimeout: ‘5 minutes’, }); export async function onboardingWorkflow(customerId: string) { await sendWelcomeEmail(customerId); await processPayment(customerId); await sendConfirmation(customerId); } Activities They are the individual, specific tasks that the workflow tells them to do, like making a database call or sending an email. Activities do the actual work. Each scene (activity) might succeed or fail. Example: “Send welcome email” or “Charge credit card”. // activities/index.ts export async function sendWelcomeEmail(customerId: string) { console.log(`Sending welcome email to ${customerId}`); } export async function processPayment(customerId: string) { console.log(`Processing payment for ${customerId}`); } export async function sendConfirmation(customerId: string) { console.log(`Sending confirmation email to ${customerId}`); } Workers Workers are the machines that run your code, They are programs you deploy on your own servers or in the cloud. These basically executes the script. If a worker stops, another can take over – the movie continues. Example: A failed camera crew doesn’t stop the movie. // worker.ts import { Worker } from ‘@temporalio/worker’; import * as activities from ‘./activities’; import * as workflows from ‘./workflows/onboardingWorkflow’; async function runWorker() { const worker = await Worker.create({ workflowsPath: require.resolve(‘./workflows/onboardingWorkflow’), activities, taskQueue: ‘onboarding-queue’, }); await worker.run(); // Keeps polling task queue and executing tasks } runWorker().catch((err) => { console.error(‘Worker failed:’, err); process.exit(1); }); Task Queues A Task Queue in Temporal is like a waiting room for tasks. When a Workflow needs to perform an Activity or continue its own logic, it places a task on a specific queue. Workers are constantly listening to these queues, and when they see a new task, they grab it and execute the corresponding code. This mechanism acts as a simple, powerful way to connect workflows and workers, ensuring that tasks are distributed and processed reliably. Example: “Scene 5: charge payment – waiting for available crew.” // client.ts import { Connection, WorkflowClient } from ‘@temporalio/client’; import { onboardingWorkflow } from ‘./workflows/onboardingWorkflow’; async function startWorkflow() { const connection = await Connection.connect(); const client = new WorkflowClient({ connection }); const handle = await client.start(onboardingWorkflow, { args: [‘customer-123’], taskQueue: ‘onboarding-queue’, // This maps to where the worker is polling workflowId: ‘onboarding-workflow-customer-123’, }); console.log(`Started workflow ${handle.workflowId}`); } startWorkflow().catch(console.error); Handling Failures, Retries, and Timeouts Gracefully Failure are everywhere in distributed systems – APIs go down, services restart, workers crash. In most systems, you have to glue together retry logic, persistence, and timeout tracking manually. Temporal handles all of this out-of-the-box, with very little configuration. Automatic Retries By default, Temporal retries failed Activities automatically. If your activity throws an error or the worker crashes mid-execution, Temporal catches it and retries based on a built-in policy. You don’t have to write try/catch, backoff logic, or state recovery. Example: // activities.ts export async function unstableActivity() { if (Math.random() < 0.5) { throw new Error('Random failure'); } console.log('Activity succeeded!'); } // workflow.ts import { proxyActivities } from '@temporalio/workflow'; import * as activities from '../activities'; const { unstableActivity } = proxyActivities({ startToCloseTimeout: '10s', // required }); export async function retryDemoWorkflow() { await unstableActivity(); // Temporal will retry this on failure } Custom Retry Policies You can configure retry behavior with options like: Max attempts Backoff intervals Retryable/non-retryable error types Example: Custom retry configuration const { flakyTask } = proxyActivities({ startToCloseTimeout: '10s', retry: { maximumAttempts: 5, initialInterval: '1s', backoffCoefficient: 2, nonRetryableErrorTypes: ['ValidationError'], }, }); | Now flakyTask will retry 5 times with exponential backoff (1s, 2s, 4s, 8s…) unless it throws ValidationError. Timeouts (Per Activity […]

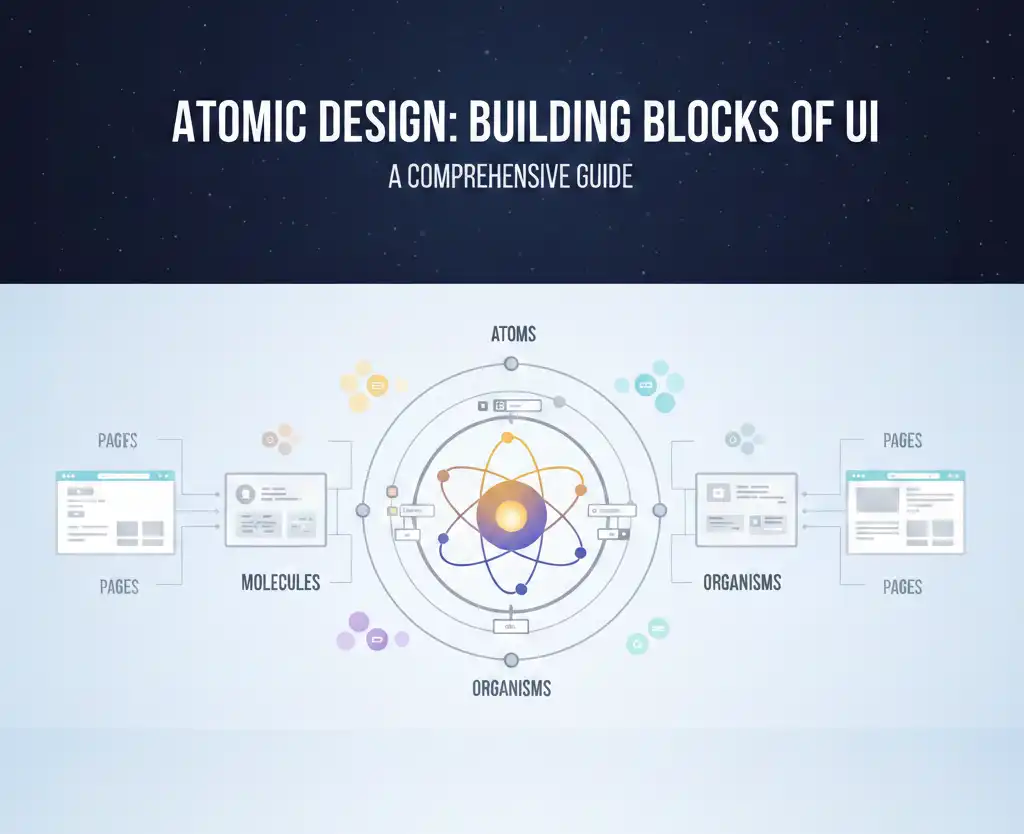

Atomic Design Pattern: A Deep Dive into Scalable UI Architecture

As modern web and mobile applications continue to evolve in complexity, creating scalable, maintainable, and reusable user interfaces is more important than ever. Choosing the right UI architecture pattern can make or break your development workflow. One of the most structured and increasingly popular methodologies is the Atomic Design pattern, introduced by Brad Frost. But how does it compare with other widely-used structuring patterns like feature-based architecture, flat component structures, or the smart/dumb component pattern? In this in-depth post, we’ll compare Atomic Design with other UI structuring methodologies, explore its benefits and trade-offs, and provide guidance on when and how to implement it effectively in your own projects. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of why Atomic Design might be the better choice—especially for large-scale, design-system-driven applications. And if you’ve ever cried while refactoring a spaghetti mess of components, this one’s for you. Understanding Atomic Design: A Quick Recap Atomic Design is a methodology for thinking about interfaces in a hierarchical and modular way, inspired by chemistry. It divides the user interface into five distinct levels: 1. Atoms These are the basic building blocks of the UI, like HTML elements (label, input, button, etc.) or simple React Native components. They are highly reusable and represent the most fundamental level of design. Think of them like Lego bricks or the socks you never find in pairs. 2. Molecules Molecules are combinations of atoms that work together as a unit. An example might be a search field consisting of a label, input field, and submit button. It’s like a sandwich—bread (input), cheese (label), and mayo (button). Delicious and functional. 3. Organisms Organisms are more complex UI sections made up of groups of molecules and/or atoms. A navigation bar, user profile card, or product list is typically an organism. Basically, if it starts to resemble something a user might recognize, it’s probably an organism. 4. Templates Templates focus on page structure. They define the layout using organisms, without tying them to specific content. Imagine a floor plan of a house before the furniture is moved in—structure without personal clutter. 5. Pages Pages are the most concrete implementation, combining templates with real data to represent specific screens or routes. Now the couch is in, the posters are hung, and someone spilled coffee on the carpet. Common UI Structuring Patterns: A Comparison Before diving deeper into why Atomic Design might be better, let’s look at other common UI architecture patterns and how they compare. 1. Flat Component Folder Structure This approach organizes components by type or general function. You might see folders like components/, containers/, screens/, etc. It’s simple and easy to start with, but becomes messy and hard to scale as your application grows. Cons: Simple to understand Easy for small apps or MVPs Cons: Poor scalability Imagine your app grows from 5 to 200 components. It becomes impossible to tell which screen or feature uses which component, and you end up scrolling like a maniac or relying on search for everything. Hard to maintain with growing component count You have 4 different modals: LoginModal, InfoModal, DeleteModal, and ShareModal—all dumped in one components/ folder. Now someone wants to refactor all modals to have a common footer. Good luck finding and updating them without breaking things accidentally. Difficult to ensure reusability Your team creates three buttons: PrimaryButton.tsx BlueButton.tsx CTAButton.tsx They all look 80% the same, but no one noticed because they’re scattered in a huge folder. Now you have three almost-identical components—and three places to fix a padding bug. Yikes. 2. Feature-Based Folder Structure This organizes code by feature or domain. For example, you might have folders like features/auth/, features/dashboard/, etc., each containing its own components, hooks, and logic. Pros: Aligns with business logic Easier to scale and delegate work in large teams Encourages separation of concerns Cons: UI component reuse across features can be more difficult You build a UserAvatar inside the dashboard/ feature. Later, the chat/ feature needs the exact same component. But instead of reusing it, someone copies it into chat/components/UserAvatar.tsx. And now… you maintain it in two places. Often duplicates similar UI elements Each feature builds its own Card.tsx component: dashboard/components/Card.tsx auth/components/Card.tsx billing/components/Card.tsx They differ slightly in margin, but now your design system is totally fragmented. And when the designer changes the card border-radius? Yep—you’ll have to update five versions manually. Hope you like regex. 3. Smart/Dumb Component Separation This pattern separates components into: Smart components (containers) – Handle logic, data fetching, and state. Dumb components (presentational) – Focus solely on UI and props. Pros: Encourages separation of concerns Makes UI easier to test and reason about Cons: No specific structure for organizing components You follow the smart/dumb split, so your folder looks like: components/ containers/ ProductListContainer.tsx presentational/ ProductList.tsx …but then someone adds ProductCard, and another dev adds ProductCardContainer, and now you’re wondering if it belongs with the card or in containers? Without additional structure like “atoms/molecules” or “features,” things get muddy real quick. Doesn’t inherently support design systems or visual hierarchy You want to align with Figma components, where designers created: Button ButtonGroup Card FormSection But your dumb components don’t follow the same visual hierarchy. Some dumb components are deeply nested, some are top-level, and there’s no sense of whether they’re foundational or composite. It’s hard for new developers or designers to see how the pieces fit together—and easy to break consistency. Atomic Design: A Pattern That Bridges Design and Development Unlike the above patterns, Atomic Design is visually driven and aligns closely with modern design tools (e.g., Figma, Sketch). It’s particularly useful when building design systems, component libraries, or large-scale applications with a high degree of UI reuse. It excels when: You’re building a design system Your app has hundreds of components You need strong collaboration with designers You want structured reuse across domains Real World Example: The Login Form Atoms: Input, Label, Button Molecule: Labeled input field (label + input) Organism: Entire login […]